Elizabethan Sermon & Evensong: Event Write-Up

This blog post is about the upcoming reconstruction we are holding at St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield on the 15th November at 6pm 2026.

Introduction

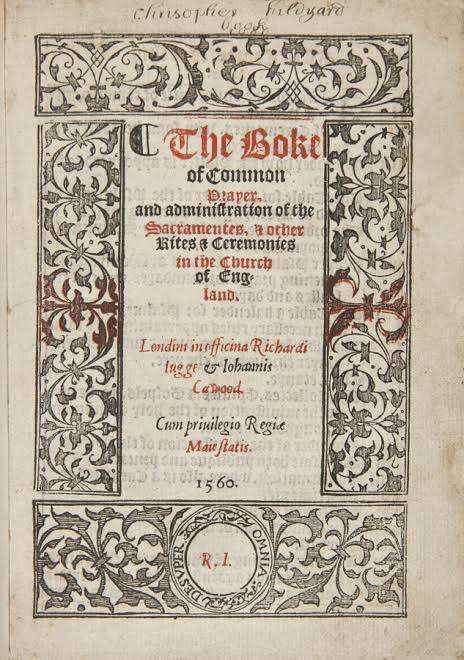

This Thursday at 6pm, we will be reconstructing Evensong according to the Elizabethan Prayer Book of 1559. This is by far the most Protestant of any of our reconstructions to date. There will be no vestments beyond surplices, no incense, and much less chanting. The service will be preceded by a sermon. The sermon in question describes itself as follows –

A sermon preached at St. Maries in Oxford, the 17. day of November, 1602. in defence of the Festivities of the Church of England, and namely that of her majesties Coronation. By John Howson Doctor of Divinity, one of her highness Chaplains, and Vicechancellor of the University of Oxford.

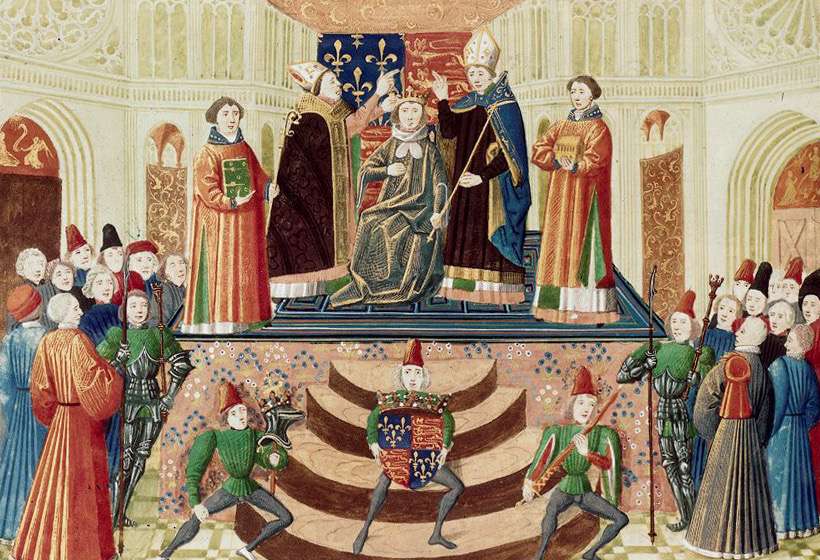

The sermon brings out the nature of our liturgical dichotomy – this sermon is written firmly under Protestant rule. The last memories of Mary I’s brief return to the Papacy were beginning to fade, and the Church of England was looking increasingly stern, and austere, increasingly ready for the liturgical revolution brought on by the so-called Laudians. And yet, the events it describes, the Coronation, are decidedly Medieval. Elizabeth was the last English monarch to be crowned according to the traditional Medieval rites, the last English monarch to be crowned with the monks of Westminster present – not terribly Protestant sounding. The services of the Elizabethan Chapel Royal were likened by continental guests to Roman Catholic services, the settlement she created, though perhaps more Reformed than she may have wished (though we will never really know), was one that allowed, tolerated and in reality, probably encouraged a more conservative liturgical style. Elizabeth issued injunctions requesting that surviving choral establishments be retained. The beginning of her reign saw the production of a number of partbooks and musical publications. The more Protestant of the Bishops bemoan their clergy “counterfeiting” the old mass, just as they did under Edward VI. Puritan critics of the religious settlement had quite the litany of complaints. They compared the surplice to the garments of the priests of Isis, and the antiphonal recitation of psalms to tennis. But for every Puritan critic, there were those who took a more old-fashioned view, such as George Herbert, who, as well as being a regular attendee of choral evensongs such this one, included in his Musæ Responsoriæ a poetic defence of the surplice amongst other aspects of the Church of England’s more conservative retentions. Although poverty, drove a lot of parishes towards a style of worship somewhat more ascetic than Elizabeth may have wished, the more conservative style this evensong will demonstrate, would likely have taken place, especially in urban areas were musically literate singing-men were readily available.

The Liturgy

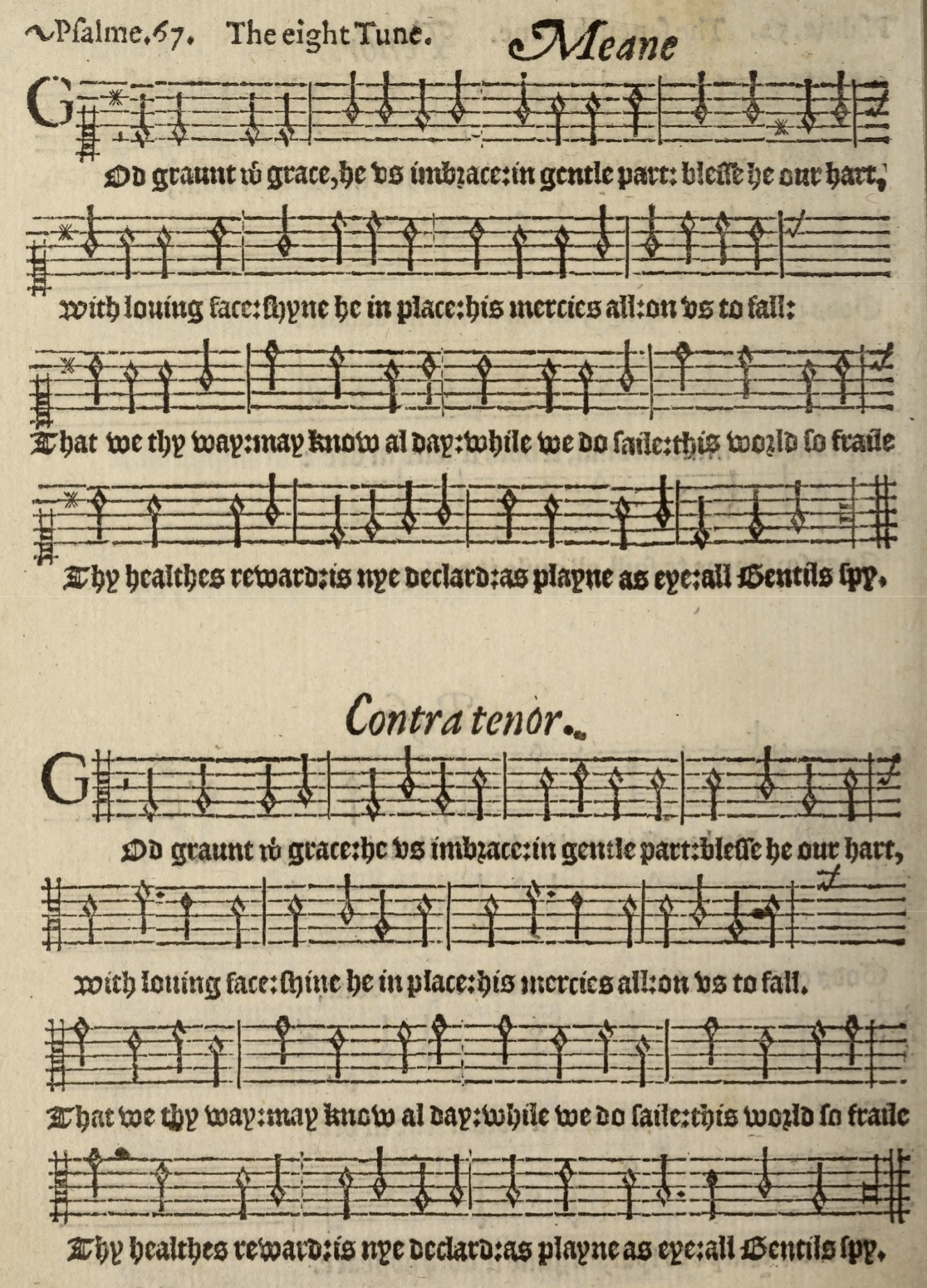

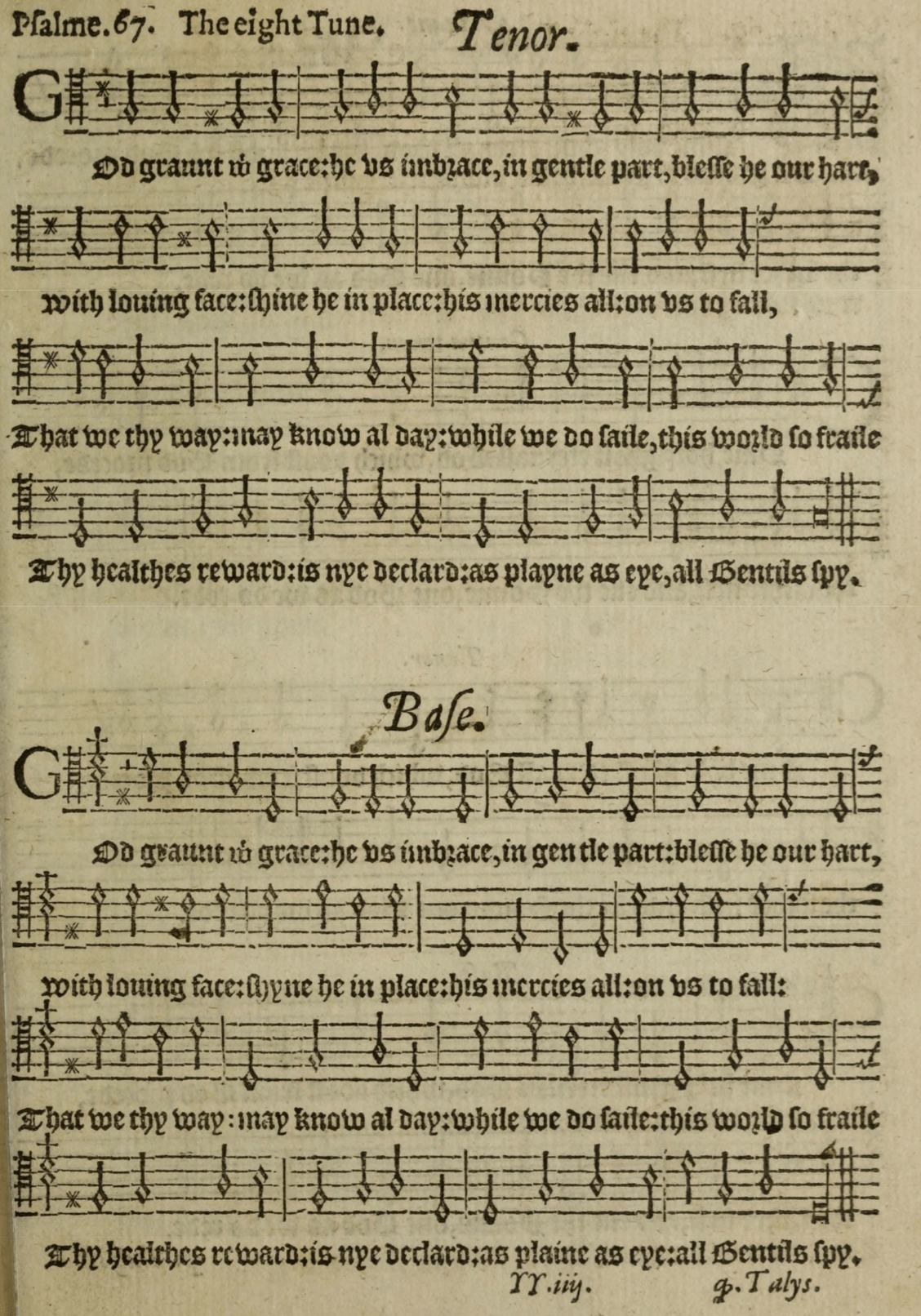

The service will open with a metrical psalm, immediately before the sermon. This is the most ostensibly Protestant element of today’s service. It is Archbishop Parker’s translation of Psalm 67, and the tune is taken from Thomas Tallis’ imaginably named Tunes for Archbishop Parker’s Psalter of 1567. This tune, now known as Tallis’ Canon is probably the most famous musical survivor in modern hymnody of the metrical psalmody that was so unanimous before Tractarianism. Although, in its original version, this tune is slightly different. Curiously, Elizabeth seems to have disapproved of metrical psalms. They did not gain so much traction in her own Chapel Royal as they did in parishes. It smacked of European Calvinism, and Calvinists considered a regent queen inappropriate. However, the growing popularity of metrical psalms was impossible to stop, the increasingly Protestant body of clergy seem to have supported their use. Like anthems, metrical psalms were not supposed to be used in the liturgy. As such, the psalm is placed before the sermon. Psalms surrounding sermons appear to have been a commonplace. However, as our reconstruction may demonstrate, the gap between a simple anthem and a complex psalm was something of a blurred. Many anthems were somewhat homophonic, and indeed many metrical psalms were somewhat contrapuntal.

Afternoon sermons (that is, before evensong) were standard. Many clergy did not have licence to preach, and so town-dwelling people would often hear approved preachers on Sunday afternoons and other choice occasions. Interestingly, though this may seem rather Protestant, and no doubt these sermons were rather Protestant in content, hearing sermons in this way was a Medieval practice. It was common for sermons to take place as part of Sunday Vespers and Procession.

Following the sermon comes the first two of our anthems. Anthems took the place of Votive Antiphons. These typically followed Compline, which was frequently recited back-to-back with Vespers. They were normally dedicated to the Virgin Mary, but frequently also to other saints and often Christ himself. The Reformation Injunctions instructed anthems should be sung in English, and only “of Our Lord”. The new prayer book Evensong incorporated the old services of Vespers and Compline, and so, the anthem of Our Lord remained tacked thereon. The new order for Mattins, which now had acquired a form fairly analogous with Evensong, thus also acquired an anthem. In time they both came of have an anthem before. The anthem before evensong is Osbert Parsley’s This is the Day, and the anthem after evensong is a contrafactum of John Taverner’s In Nomine called O Give Thanks.

Some plainsong remains in our reconstruction. The psalms and responses are sung much as they would have been when they were in Latin. Clerks were accused of making the new liturgy sound like the old, and indeed, as already mentioned, the antiphonal recitation, so despised by Puritans, was clearly not unusual. Singing men and clergy who had grown up with and been trained on pre-Reformation liturgy would not have really known any other way to sing them.

The Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis are sung polyphonically, to Tallis’ famous Dorian Service. This simple setting gives a sense of what ferial sacred music was like. The Magnificat was sung in choral services to polyphony pre-Reformation, but the Nunc was not. There are no pre-Reformation English settings of the Nunc surviving, but plenty of the Magnificat. Therefore, the practice of setting the Nunc and pairing the canticles is something of a Reformed innovation, but rather a “high” Protestant one.

Before each of the anthems and before each of the lessons there will be short organ versets to cover the liturgical movement, as well as provided something of an introduction. The use of organ preludes to have been something of a common practice, where they had both organ and organist, on suitably important occasions up until the 19th century.

I always really admire your technical know-how!