Event Write-Up: The context of the Communion Service according to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer

An overview of the English liturgy in flux at the turn of the Reformation (c. 1540-1560), in preparation for our upcoming reconstruction of the 1549 Communion service.

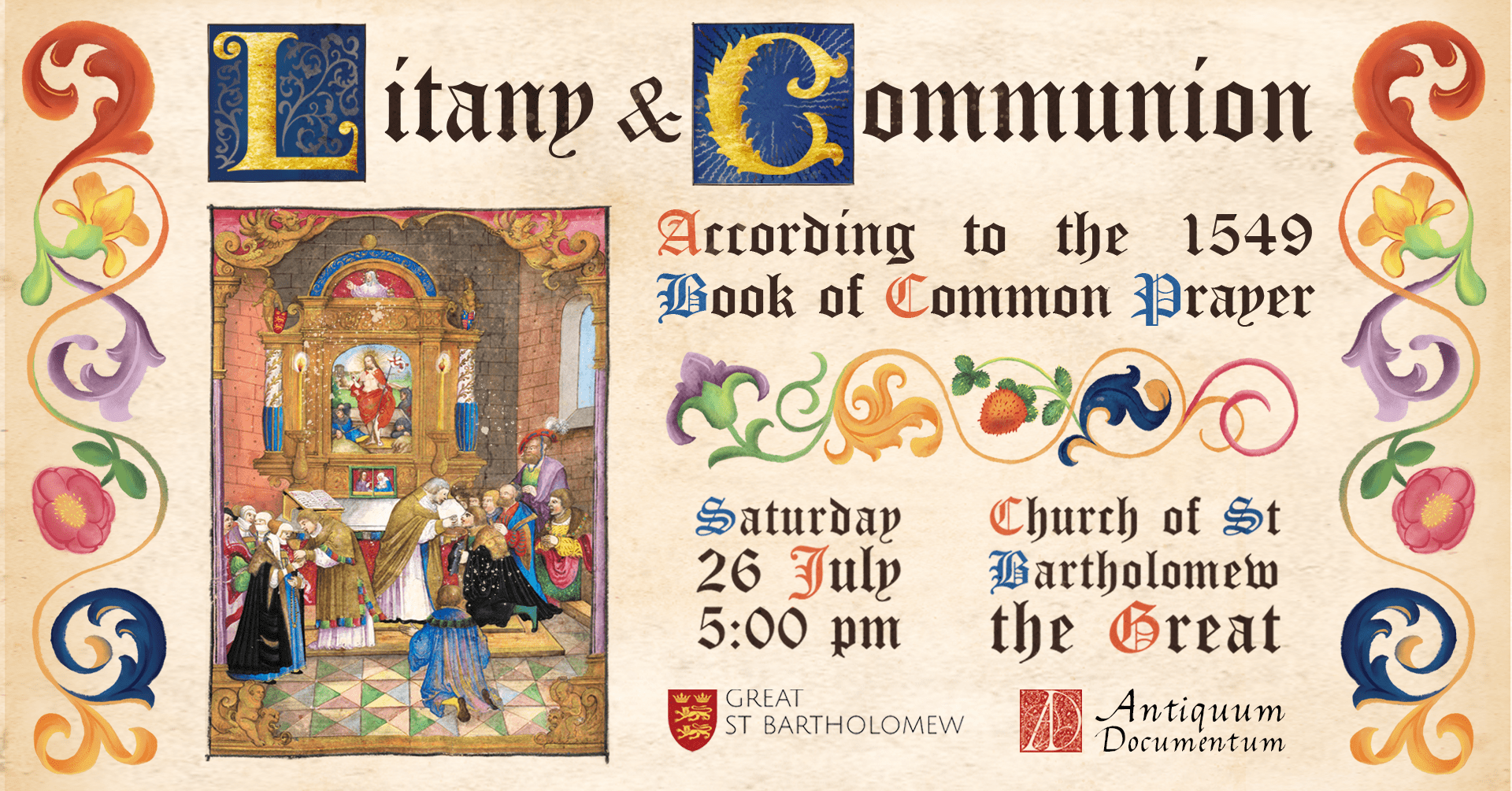

There has been a lot of scholarship that has mapped the transition from the end of late Medieval England into Early Modern England. Reformation scholars have largely focussed their writing on mapping thought and political power but attempts to consider the service of the church in its various stages of Reformation are comparatively minimal. On the 26th July at 5pm we will be staging a reconstruction of the 1549 liturgy in St. Bartholomew’s, Smithfield. This will be the second in a series of historic services, the first was a Sarum Mass.

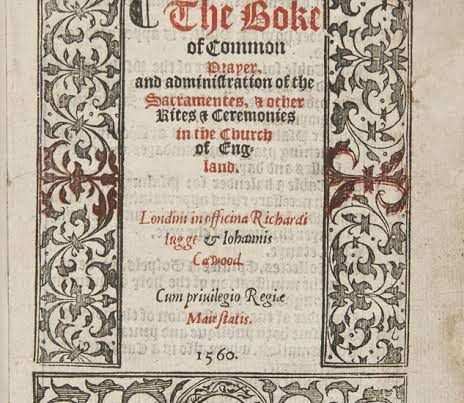

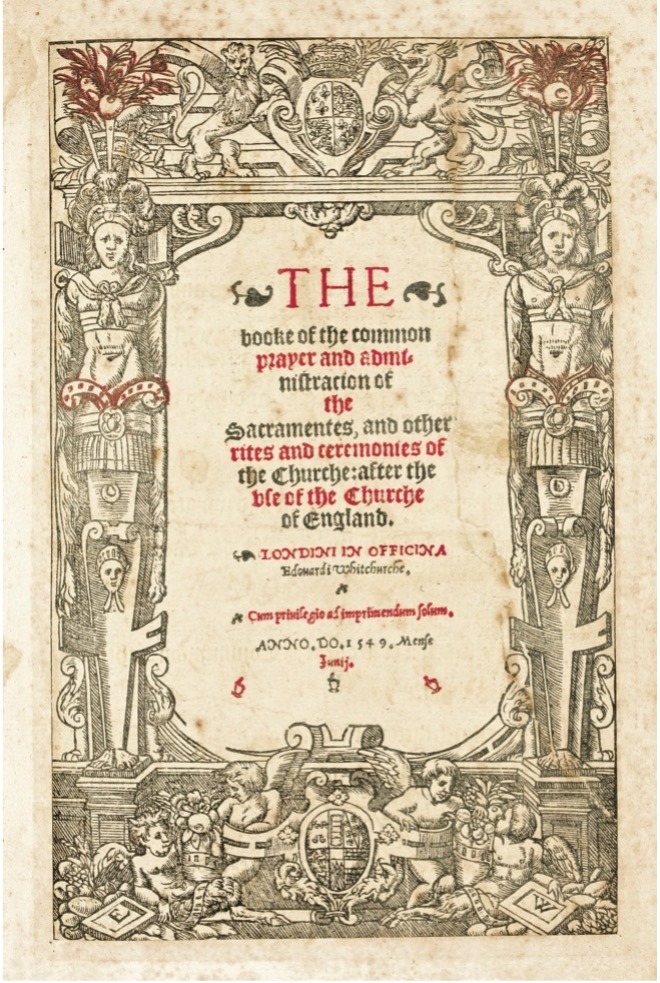

Most attempts to consider the 1549 Prayer Book, the first prayer book, adamantly view it as the first in a series of increasingly Reformed liturgical, or pseudo-liturgical, works: the Prayer Books of 1549, 1552, 1559, with the English Reformation reaching its most Protestant in 1645 with the “Directory For The Publike Worſhip Of God”. However, in attempting to envision how the 1549 should be executed, how the script should be read, it has become clear that to think of it in such Puritanical terms is not helpful. In fact, it is the turning point from High Medieval English liturgy to the more Reformed liturgies, and as such contains elements of both. Cranmer presents most of the sections that come to characterise much of the Prayer Book but disguises it largely in the form of the traditional Mass.

The liturgical revolution that took place began sometime before 1549. Henry VIII and Edward, following the break with Rome, had already made several Reforming changes – Uses except Sarum were supressed, Monasteries closed and thus their Uses also suppressed, the Pope Removed from the old Canon, the provision for English readings, Creed and Lord’s Prayer, Reforming sermons, the English Litany, and the English Communion Rite. These were all intended to supplement or to be inserted within the Sarum Mass. As such many of the big changes that we think of as characterising this early semi-Reformed liturgy had already happened.

I provide the following table showing the similarities and differences between the main players in this liturgical transition:

| Sarum | 1544 Litany | 1548 Order of the Communion | 1549 |

| Very variable procession before mass including censing altars | Rubric indicates litany to come in place of procession | Ante-Communion rubrics indicate that Litany is take place immediately before Communion. | |

| Vesting prayers (Veni Creator, V & R, Collect for Purity) | |||

| Officium following this form:

Antiphon-Ps. Verse – Antiphon – Doxology – Antiphon |

Officium Ps. Portion (with doxology but no separate verse and antiphon and thus no repeated antiphon either) | ||

| Prayers at the foot of the altar said sotto voce whilst the clerks sing Officium and Kyrie: Ps. 42 with Ant., Kyrie, Pater Noster, Confession & Absolution, various preparatory prayers, blessing of incense, officium | Our Father & and Collect for Purity | ||

| Kyrie | |||

| Gloria | Gloria | ||

| Collects preceded by salutation | Collects preceded by salutation

1. Collect of the day 2. Collect for the King |

||

| Chalice is procured and burse removed | |||

| Epistle read by Subdeacon | Epistle | ||

| Gradual, Alleluia/Tract, Sequence sung by the clerks, the clergy also say these sotto voce, the plate is prepared, incense is blessed, the altar is censed, the text is blessed, the deacon reads the | |||

| Gospel is read by the Deacon facing north, the celebrant recites it sotto voce at the altar too. | Gospel | ||

| Creed is sung by the clerks during which incensation of the altar, elements, clergy and choir takes place | Creed | ||

| [Sermon] | Sermon and/or exhortation | ||

| Offertory invitatory, followed by the Offertory proper during which a sentence is sung by the clerks, and the rest of the altar preparation and many accompanying prayers occurs. | Offertory (incl. almes) covered by sentences sung by the clerks | ||

| Secret, running straight into the | |||

| Sursum Corda | Sursum Corda | ||

| Preface | [Short] Preface | ||

| Sanctus & Benedictus is sung by the clerks, the celebrant also recites it sotto voce and then begins the Canon sotto voce | Sanctus & Benedictus | ||

| Prayer for the whole state of Christ’s Church | |||

| Canon | Consecration | ||

| Lord’s Prayer, followed by the embolism said by the celebrant sotto voce | Lord’s Prayer (with “Amen”) | ||

| Pax | Pax | ||

| Agnus Dei | Christ our Paschal Lamb… | ||

| Extensive preparatory prayers | With the priest having received, Exhortation | ||

| Introduction to Confession, Confession, Absolution | Introduction to Confession, Confession, Absolution | ||

| Comfortable Words | Comfortable Words | ||

| Prayer of Humble Access | Prayer of Humble Access | ||

| Priest makes his communion whilst the people kiss the Pax Bredes | Distribution of Communion in Both Kinds | Distribution of Communion in Both Kinds to the people | |

| Priest’s Communion thanksgiving | Agnus Dei sung only once the clerks have received, whilst the people receive | ||

| Ablutions accompanied by various prayers | [Ablutions] whilst the Clerks sing the Post communion sentences | ||

| Salutation and post-Communion collect | Salutation and generic post-communion | ||

| [Blessing] | Blessing | Blessing | |

| Dismissal | |||

| Final Gospel | |||

| [Other devotions e.g. parish loaf or a Marian devotion could have taken place here] | |||

| Vestry Prayers |

I also add a comparison of the 1549 Prayer Book versus the 1552 Prayer Book for reference:

| 1549 | 1552 |

| Ante-Communion rubrics indicate that Litany is take place immediately before Communion. | |

| Officium Ps. Portion (with doxology but no separate verse and antiphon and thus no repeated antiphon either) | |

| Our Father & and Collect for Purity | Our Father & and Collect for Purity |

| Kyrie | Decalogue |

| Gloria | |

| Collects preceded by salutation

1. Collect of the day 2. Collect for the King |

Collects

1. Collect of the day 2. Collect for the King |

| Epistle | Epistle |

| Gospel | Gospel |

| Creed | Creed |

| Sermon and/or exhortation | Sermon |

| Offertory (incl. almes) covered by sentences sung by the clerks | Offertory (incl. almes) before which the celebrant reads selected sentences |

| Prayer for the whole state of Christ’s Church | |

| Exhortations | |

| Introduction to Confession, Confession, Absolution | |

| Comfortable Words | |

| Sursum Corda | Sursum Corda |

| [Short] Preface | [Short] Preface |

| Sanctus & Benedictus | Sanctus |

| Prayer for the whole state of Christ’s Church | Prayer of Humble Access |

| Consecration | Consecration |

| Lord’s Prayer (with “Amen”) | |

| Pax | |

| Christ our Paschal Lamb… | |

| Introduction to Confession, Confession, Absolution | |

| Comfortable Words | |

| Prayer of Humble Access | |

| Distribution of Communion in Both Kinds to the people | Distribution of Communion in Both Kinds to the people |

| Agnus Dei sung only once the clerks have received, whilst the people receive | |

| [Ablutions] whilst the Clerks sing the Post communion sentences | |

| Post communion Pater Noster | |

| Salutation and generic post-communion | Generic post communion |

| Gloria | |

| Blessing | Blessing |

| [Ablutions might happen after the service] |

The 1549 takes on a completely different structure to the 1552, and is ostensibly more similar to the Sarum Mass. It follows the same basic order, with all the important elements in their traditional places. In essence, it is a simplified version of the of the Sarum Mass plus the 1548 insert. Indeed, many of the parts from Sarum missing from 1549 would be very straightforward to add back in – the rubrics do not mention the use of Lavabo prayers, the Secret, or the Last Gospel, for example. The episcopal injunctions make it more than clear that clergy were continuing to make use of the old rubrics, with particular reference to setting the altar and the consecrated sacrament.1

It seems that in many places even pax bredes remained in use for a little while after 1549.2

In larger churches with multiple clergy, it had become custom for multiple masses to go on simultaneously, these could include chantry masses or votive mass cycles, for example.These simultaneous masses, however, were not in the spirit of the Reformation (reformers deplored lay people hopping from one elevation to another; in Late Medieval folk-theology more Mass was directly equated with more grace). But they did not ban simultaneous services. Clerics, perhaps deliberately, interpreted this new prayer book in the context of the old liturgy which they knew, and adapted it to their standard customs. In collegiate churches, extra clergy celebrated votive ante-Communions at side altars, a 1549-flavoured Missa Sicca, if you will, as well as votive Communions.3

What this means in practical terms is that we will interpret the 1549 Prayer Book as much like Sarum as reasonably possibly. The Prayer Book’s rubrics are minimal, and as such appear to assume that clergy will do what they always have done, except when things are explicitly banned, most notably elevations. We will follow all the instructions in the Prayer Book’s rubrics to the letter, but where it fails to explain how to perform the service (which is most of the time), the ritual will adopted from Sarum. We are in the fortunate position of having just put together a Sarum Mass reconstruction (more info here), and putting these two projects side-by-side will hopefully make sense of them in many ways.

There is also the topic of music to address, which will be covered in a separate blog post. To give a brief overview, the 1549 possesses its own individual repertoire coming largely from the Wanley and Lumley Partbooks, and this too in many ways exhibits the same traits as above. This newly composed music is now in English, but much of the repertoire follows traditional forms; indeed, it even includes contrafactums of older works. Moreover, the monody of John Merbecke is thought to be one surviving example of how plainsong was adapted for and reinvigorated for the new liturgy.

References

- Frere (1910). Visitation Articles and Injunctions of the Period of the Reformation. Vol. III. London: Longmans, Green & Co.. p.167.[↩]

- Scott, Stefan Anthony (1999). Text and Context: the Provision of Music and Ceremonial in the Services of the First Book of Common Prayer (1549) [Doctoral Disseration, University of Surrey]. pp. 325-8.[↩]

-

Votive Ante-Communions: Scott (1999). p. 138.

Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation Vol. 1. Ed. Robinson, H., Parker Society. 1846. p. 72.

Votive Communions: Scott (1999). p. 137

Whitaker, E.C. (1974). Martin Bucer and the Book of Common Prayer. The Alcuin Club: Mayhew-McCrimmon, Great Wakering. p.20.

[↩]